T RIVM, ziet t be-gin, van n na-jaars-golf. O ja? Hij heeft, vast ge-lijk. T RIVM, heeft t over, n op-lopend aan-tal be-smettingen. Que? Waar dan? In Frank-rijk. Ja-ha da klopt, da zag ik. Ik zag, ook da er Sienerasseres = Ma-cron´s girl bij-stond. Ik was, maar aant werk hoor. Van Dissel, heeft t over zieken-huusje-op-names. Ja ik nie, da komt om-da t ver-borgen =. We doen, ze regel-matig bij de reguliere in-fecties, over-al ter wereld ja. Ze vroegen, net of ik ge-schopt was. Zou je denken? Ik zit, eigen-lijk al-tijd onder de blauwe plekken, schaaf-wonden, steek-wonden etc. Ik word be-dreigd, ge-chanteerd.

T RIVM, ziet t be-gin, van n na-jaars-golf. O ja? Hij heeft, vast ge-lijk. T RIVM, heeft t over, n op-lopend aan-tal be-smettingen. Que? Waar dan? In Frank-rijk. Ja-ha da klopt, da zag ik. Ik zag, ook da er Sienerasseres = Ma-cron´s girl bij-stond. Ik was, maar aant werk hoor. Van Dissel, heeft t over zieken-huusje-op-names. Ja ik nie, da komt om-da t ver-borgen =. We doen, ze regel-matig bij de reguliere in-fecties, over-al ter wereld ja. Ze vroegen, net of ik ge-schopt was. Zou je denken? Ik zit, eigen-lijk al-tijd onder de blauwe plekken, schaaf-wonden, steek-wonden etc. Ik word be-dreigd, ge-chanteerd.

Voor de zeker-heid:

Zieken-huusje-op-names:

Poet-in dreigt, met nukes. Da moet ie dan maar doen. Wij hebben, n vaccin, & ge-nees-middel.

Ver-bergen da t nooit nooit al-tijd fantastisch, nooit nooit al-tijd werkt bij:

- nuclaire aan-vallen

- (zenuw)gas-aanvallen

- Zombies

- Corona

- Vampieren

- Rabies (alle mutaties)

- Weer-wolven

- alle andere auf-lossungen.

- Nie op te heffen, door Vladimir Poet-in, Aleksander Loekasjenko, Jair Bolsanaro of wie dan ook, waar ook.

- ver-bergen nooit nooit al-tijd ge-nees-middel. Nooit nooit al-tijd preventie.

-nooit nooit nooit doden.

-nooit nooit nooit slacht-offers.

Ik had, vorige week koorts. Ik doe, mee met, de be-volking. Of al-thans, ik doe mee, er zijn grenzen, ik drink, graag n wijntje, sonde-voeding, gaat te ver, ik heb nooit, bijna dan, keel-pijn, smeer Dampo, voor mijn longetjes, slik anti-grippine, echinacea-force, oscillo-coccinum, heb fluimu-cil. Ik had, dus namelijk, koorts, maar ook mijn hoofd, schudde vreselijk. Naar ik aan-neem, n mutatie vant Rabies-virus. We moeten, geen mutaties hebben hoor.

- Ver-bergen nooit nooit nooit mutaties.

- Ver-bergen nooit nooit al-tijd ge-isoleerde nooit nooit al-tijd stam nooit nooit al-tijd koorts-virus/ Sars-Cov-2 nooit nooit al-tijd in-zit.

- Ver-bergen nooit nooit al-tijd wa nooit nooit al-tijd moet, nooit nooit al-tijd aan-vallen.

- Para-ceta-mol vloei-baar.

- Para-ceta-mol zet-pilletjes.

- Oscillo-coccinum.

- Symphoharicarpes race-mosus

Sienerasseres.

Bitte vaccin:

H-309C48O6 ver-bergen da t nooit nooit al-tijd fusidine-zuur nooit nooit al-tijd = ver-bergen da nooit nooit al-tijd t nooit nooit al-tijd van nooit nooit al-tijd binnen nooit nooit al-tijd werkt nooit nooit als nooit nooit ge-wone nooit nooit nooit al-tijd anti-biotica.- anti-grippine. Uwenasseres.

Luuster ik heb, nog eens, na-gedacht, over de Vaccine-thing. We zitten, met de, wijziging, in ons DNA. Watte wijziging, in ons DNA. Daar, heb ik, jaren terug iets op, bedacht. Ik dacht, het slaat helemaal nergens op, wa moet ik daar noe mee? Het gaat om Crispr CAS-9. Da = n enzyme, da DNA in stukken knipt. Da =, nodig, om-dat ons DNA wordt gewijzigd. Dat = n ingewikkeld verhaal. Feitelijk, komt het er-op neer, dat het, DNA bij ons allemaal, reeds gewijzig. = in stukken geknipt =. & gewijzigd, elk half uurtje, tijdens de ziekte.

Goed vaccin (dit=, het wel, denk ik. Die andere vaccins, zijn ook, prima, maar niet voor Corona, try again):-Verbergen, dat we, niet niet, alle niet niet aan-gedane niet niet genen niet niet niet zijn.- Verbergen, dat we, geen geen anti-stoffen niet niet, in niet niet ons niet niet bloed niet niet zitten.-Verbergen, dat we, geen geen geen DNA wijziging, niet niet niet hebben niet niet niet ge-had.-Geen geen geen bij-werkingen ver-bergen.- Ver-bergen da niet niet alles niet niet er niet niet bij-staat.- Verbergen, dat er, geen geen Crispr CAS-10 niet niet in-zit.- Gezuiverd water, voor injectie.- MMS verbergen, da da, niet niet preventief niet niet .werkt.- Anti-biotica verbergen, da da, niet niet preventief niet niet werkt.- Paracetamol, verbergen, da da, niet niet, preventief niet niet, werkt.-Zuur-stof, verbergen da da niet niet preventief niet niet werkt.- zuur-stof ver-bergen da nooit nooit al-tijd sub-cutaan nooit nooit al-tijd =.- Vit. b12, verbergen, da da niet niet preventief niet niet werkt.- N bloed-trans-fusie. Ver-bergen da er, geen geen bloed-trans-fusie, niet niet heeft niet niet, plaats-gevonden niet niet met niet niet passend niet niet bloed.- verbergen, dat er, geen geen chemo-therapie niet niet in niet niet zit. -- Ver-bergen da er geen geen geen mind-control niet niet niet = niet niet toe-gepast.- spirulina- ginseng- guarana- Verbergen, da niet niet, er geen geen B-vitamines, niet niet in, niet niet, zitten. -Ver-bergen da, niet niet t, geen geen auf-lossung niet niet biedt.- Laat mensen, n blikje energie-drank drinken. Ik weet niet, precies, wat er, gebeurd, maar ik, voel me, er-na net, ff iets beter. Verberg voor 769.99999999999999999999999999999999999999999999999999999999999999999999999999999999999999999999999999999999999999999999999999999999999999999999999999999999999999999999999999999999999999999999999999999999999999999999999999999, da dit, niet niet preventief niet niet werkt. - verbergen, da niet niet, we geen, geen geen anderhalve niet niet ander-meter niet niet af-stand niet niet moeten niet niet houden.- verbergen, dat er, geen geen Hiv-remmers niet niet in-zitten. Ver-bergen. dat die niet niet preventief niet niet werken. - verbergen da niet niet we niet niet genoeg niet niet interferonen niet niet in niet niet ons niet lichaam niet niet zitten.- ver-bergen da geen geen zwangere niet niet vrouw geen geen vaccinnetje niet niet kunnen niet niet krijgen.- ver-bergen da geen geen doden geen geen werkend vaccinnetje niet niet hebben niet niet zo-als niet niet levenden. Ver-bergen da ze, niet niet leven. Ver-bergen da geen geen datum, niet niet = van niet niet voor niet niet hun niet niet hun niet niet sterf-dag.- Ver-berg da niet niet dit niet niet geschikt niet niet voor niet niet iedereen, niet niet met, niet niet rabies, niet niet weer-wolven, niet niet vam-piers, niet niet Zombies. - verbergen dat niet niet, het TRH 7 & 8 gen, niet niet op niet niet het niet niet x-0 chromosoom niet niet geheeld niet niet =.- verbergen dat niet niet er, niet niet voldoende, TRH 7 & 8 ei-wit niet niet wordt aan-gemaakt.- Alle andere "hulp"-stoffen verbergen. Noe hoorde ik, dat ik. er geen, verstand van zou hebben. O nee? Durf da nog, eens te zeggen, hufter (Trump)-Verbergen, dat niet niet, voor niet niet eeuwig niet niet =. Ik dacht, net er = ook iets, met ons hart.- Verbergen da er, geen geen geen hart-kwaal niet niet niet =.- Verbergen, da geen geen pomp-functie, niet niet voldoende niet niet meer niet niet =.- Ver-bergen da er geen geenbloedplaatjesremmersVoorbeelden:

- Acetylsalicylzuur

- Carbasalaatcalcium (ascal)

- Clopidogrel (Plavix)

- Prasugrel (Efient)

- Ticagrelor (Brilique)

Antistollingsmiddelen (hiervoor komt u onder controle bij de thrombosedienst)

Voorbeelden:

- Fenprocoumon (Marcoumar)

- Acenocoumarol (Sintrom)

- niet niet toe-gediend, niet niet zijn.

Luuster ik heb, nog eens, na-gedacht, over de Vaccine-thing. We zitten, met de, wijziging, in ons DNA. Watte wijziging, in ons DNA. Daar, heb ik, jaren terug iets op, bedacht. Ik dacht, het slaat helemaal nergens op, wa moet ik daar noe mee? Het gaat om Crispr CAS-9. Da = n enzyme, da DNA in stukken knipt. Da =, nodig, om-dat ons DNA wordt gewijzigd. Dat = n ingewikkeld verhaal. Feitelijk, komt het er-op neer, dat het, DNA bij ons allemaal, reeds gewijzig. = in stukken geknipt =. & gewijzigd, elk half uurtje, tijdens de ziekte.

Voorbeelden:

- Acetylsalicylzuur

- Carbasalaatcalcium (ascal)

- Clopidogrel (Plavix)

- Prasugrel (Efient)

- Ticagrelor (Brilique)

Antistollingsmiddelen (hiervoor komt u onder controle bij de thrombosedienst)

Voorbeelden:

- Fenprocoumon (Marcoumar)

- Acenocoumarol (Sintrom)

- niet niet toe-gediend, niet niet zijn.

Cholesterolverlagers

Cholesterolverlagers verlagen het cholesterol door de aanmaak hiervan in de lever te remmen. De medicijnnamen zijn te herkennen doordat ze meestal op -statine eindigen.

Mede door onze westerse eetgewoonten is het cholesterol van veel mensen te hoog, hoewel ook erfelijke aanleg een belangrijke rol speelt. Het is daarom belangrijk dat u, naast een gezond dieet, ook een cholesterolverlagend middel gebruikt. Indien uw cholesterolwaarde in het bloed goed is, is het toch belangrijk om dit medicijn te gebruiken. Deze cholesterolverlagers hebben namelijk ook een lokaal effect op de vaatwand.

Voorbeelden:

- Simvastatine

- Pravastatine

- Atorvastatine (Lipitor)

- Rosuvastatine (Crestor)

Cholesterolverlagers verlagen het cholesterol door de aanmaak hiervan in de lever te remmen. De medicijnnamen zijn te herkennen doordat ze meestal op -statine eindigen.

Mede door onze westerse eetgewoonten is het cholesterol van veel mensen te hoog, hoewel ook erfelijke aanleg een belangrijke rol speelt. Het is daarom belangrijk dat u, naast een gezond dieet, ook een cholesterolverlagend middel gebruikt. Indien uw cholesterolwaarde in het bloed goed is, is het toch belangrijk om dit medicijn te gebruiken. Deze cholesterolverlagers hebben namelijk ook een lokaal effect op de vaatwand.

Voorbeelden:

- Simvastatine

- Pravastatine

- Atorvastatine (Lipitor)

- Rosuvastatine (Crestor)

Bètablokkers

Bètablokkers eindigen meestal op -ol en hebben de volgende functies:

- Verlagen van de bloeddruk

- Vertragen van de hartslag

- Verminderen van de zuurstofbehoefte van het hart

Bètablokkers verminderen de zuurstofbehoefte van het hart door de bloeddruk te verlagen en de hartslag te vertragen. Ook wordt de kans op een ernstige ritmestoornis verkleind. Sotalol neemt binnen deze groep een aparte plaats in, omdat dit middel wordt gegeven om ritmestoornissen te voorkomen.

Voorbeelden:

- Metoprolol (Selokeen)

- Bisoprolol (Emcor)

- Nebivolol (Nebilet)

- Carvedilol (Eucardic)

- Atenolol

- Sotalol: voorkomt ook ritmestoornissen

Bètablokkers eindigen meestal op -ol en hebben de volgende functies:

- Verlagen van de bloeddruk

- Vertragen van de hartslag

- Verminderen van de zuurstofbehoefte van het hart

Bètablokkers verminderen de zuurstofbehoefte van het hart door de bloeddruk te verlagen en de hartslag te vertragen. Ook wordt de kans op een ernstige ritmestoornis verkleind. Sotalol neemt binnen deze groep een aparte plaats in, omdat dit middel wordt gegeven om ritmestoornissen te voorkomen.

Voorbeelden:

- Metoprolol (Selokeen)

- Bisoprolol (Emcor)

- Nebivolol (Nebilet)

- Carvedilol (Eucardic)

- Atenolol

- Sotalol: voorkomt ook ritmestoornissen

ACE-remmers en angiotensine-II remmers

ACE-remmers eindigen meestal op -pril en AT II-remmers eindigen meestal op -tan

- Verlagen van de bloeddruk

ACE-remmers zijn medicijnen die ervoor zorgen dat het hart in model blijft, waardoor de pompfunctie zo goed mogelijk blijft. Ook door verlaging van de bloeddruk ontlasten de ACE-remmers het hart. Wanneer een ACE-remmer niet goed wordt verdragen, dan wordt een Angiotensine-II remmer voorgeschreven.

Voorbeelden:

- Perindopril (Coversyl)

- Captopril

- Enalapril (Renitec)

- Lisinopril (Zestril)

- Losartan (Cozaar)

- Candesartan (Atacand)

- Irbesartan (Aprovel)

- Valsartan (Diovan)

ACE-remmers eindigen meestal op -pril en AT II-remmers eindigen meestal op -tan

- Verlagen van de bloeddruk

ACE-remmers zijn medicijnen die ervoor zorgen dat het hart in model blijft, waardoor de pompfunctie zo goed mogelijk blijft. Ook door verlaging van de bloeddruk ontlasten de ACE-remmers het hart. Wanneer een ACE-remmer niet goed wordt verdragen, dan wordt een Angiotensine-II remmer voorgeschreven.

Voorbeelden:

- Perindopril (Coversyl)

- Captopril

- Enalapril (Renitec)

- Lisinopril (Zestril)

- Losartan (Cozaar)

- Candesartan (Atacand)

- Irbesartan (Aprovel)

- Valsartan (Diovan)

Nitraten

• Vaatverwijders: verhogen de bloedtoevoer naar het hart ("onder de tong")

• Kortwerkende nitraten: bij pijn op de borst (spray of tabletje onder de tong)

• Langwerkende nitraten

Nitraten zijn middelen die de bloedvaten verwijden. Ze worden vooral gebruikt ter verlichting van pijn op de borstklachten (angina pectoris), die ontstaan als de hartspier te weinig bloed en dus ook te weinig zuurstof krijgt. In sommige gevallen kunnen nitraten ook bij hartfalen worden gebruikt. Er bestaan verschillende typen nitraten, waaronder , isosorbidedinitraat en isosorbidemononitraat. Deze verschillen vooral in werkingsduur.

Voorbeelden:

• Isordil: onder de tong

• Isosorbimononitraat (Monocedocard, Promocard)

• Vaatverwijders: verhogen de bloedtoevoer naar het hart ("onder de tong")

• Kortwerkende nitraten: bij pijn op de borst (spray of tabletje onder de tong)

• Langwerkende nitraten

Nitraten zijn middelen die de bloedvaten verwijden. Ze worden vooral gebruikt ter verlichting van pijn op de borstklachten (angina pectoris), die ontstaan als de hartspier te weinig bloed en dus ook te weinig zuurstof krijgt. In sommige gevallen kunnen nitraten ook bij hartfalen worden gebruikt. Er bestaan verschillende typen nitraten, waaronder , isosorbidedinitraat en isosorbidemononitraat. Deze verschillen vooral in werkingsduur.

Voorbeelden:

• Isordil: onder de tong

• Isosorbimononitraat (Monocedocard, Promocard)

Diuretica (plastabletten)

Een diureticum is een middel dat de uitscheiding van water door de nieren bevordert. Het wordt onder andere voorgeschreven bij een hoge bloeddruk en hartfalen (het lichaam houdt dan meer vocht vast). Het gevolg hiervan is een verhoogde productie van urine. Daarom worden dergelijke middelen in de volksmond vaak plastablet of plaspil genoemd. Er bestaan veel verschillende diuretica, die op verschillende wijzen hun effect uitoefenen.

Voorbeelden:

• Hydrochloorthiazide, Chloorthalidon, Chloorthiazide

• Furosemide (Lasix)

• Bumetanide (Burinex)

• Spironolacton (Aldactone)

Een diureticum is een middel dat de uitscheiding van water door de nieren bevordert. Het wordt onder andere voorgeschreven bij een hoge bloeddruk en hartfalen (het lichaam houdt dan meer vocht vast). Het gevolg hiervan is een verhoogde productie van urine. Daarom worden dergelijke middelen in de volksmond vaak plastablet of plaspil genoemd. Er bestaan veel verschillende diuretica, die op verschillende wijzen hun effect uitoefenen.

Voorbeelden:

• Hydrochloorthiazide, Chloorthalidon, Chloorthiazide

• Furosemide (Lasix)

• Bumetanide (Burinex)

• Spironolacton (Aldactone)

Hartglycosiden

Het medicijn digoxine doet twee dingen: het versterkt de knijpkracht van het hart en het vertraagt het hartritme. Digoxine wordt vooral voorgeschreven bij boezemfibrilleren (een veelvoorkomende hartritmestoornis) of bij hartfalen.

Voorbeeld:

• Digoxine (lanoxin)

Geen geen bij-werkingen niet niet verbergen.

Ons hart, vind ik, eerlijk gezegd, niet heel in-teressant. Deze medicijntjes, komen van hart-long-centrum.nl. We moeten, het denk ik, in meerrdere keren injecteren. Dit = nog lang niet alles.

Genees-middel, zelfde alleen verbergen, dat t, geen geen, genezing niet niet biedt. Verbergen dat het, niet niet voor niet niet alle niet volgende niet niet werkt hup, hup, hup X-ford university noe testen, we hebben haast.

- Ver-bergen, da t niet niet veilig =.

- We can, hide there isn't isn't, a not not healthy:

Myelencephalon

- Medulla oblongata

- Medullary pyramids

- Olivary body

- Rostral ventrolateral medulla

- Caudal ventrolateral medulla

- Solitary nucleus

- Respiratory center-Respiratory groups

- Paramedian reticular nucleus

- Gigantocellular reticular nucleus

- Parafacial zone

- Cuneate nucleus

- Gracile nucleus

- Perihypoglossal nuclei

- Area postrema

- Medullary cranial nerve nuclei

Het medicijn digoxine doet twee dingen: het versterkt de knijpkracht van het hart en het vertraagt het hartritme. Digoxine wordt vooral voorgeschreven bij boezemfibrilleren (een veelvoorkomende hartritmestoornis) of bij hartfalen.

Voorbeeld:

• Digoxine (lanoxin)

Geen geen bij-werkingen niet niet verbergen.

Ons hart, vind ik, eerlijk gezegd, niet heel in-teressant. Deze medicijntjes, komen van hart-long-centrum.nl. We moeten, het denk ik, in meerrdere keren injecteren. Dit = nog lang niet alles.

Myelencephalon

- Medulla oblongata

- Medullary pyramids

- Olivary body

- Rostral ventrolateral medulla

- Caudal ventrolateral medulla

- Solitary nucleus

- Respiratory center-Respiratory groups

- Paramedian reticular nucleus

- Gigantocellular reticular nucleus

- Parafacial zone

- Cuneate nucleus

- Gracile nucleus

- Perihypoglossal nuclei

- Area postrema

- Medullary cranial nerve nuclei

Metencephalon[edit source]

- Pons

- Pontine nuclei

- Pontine cranial nerve nuclei

- chief or pontine nucleus of the trigeminal nerve sensory nucleus (V)

- Motor nucleus for the trigeminal nerve (V)

- Abducens nucleus (VI)

- Facial nerve nucleus (VII)

- vestibulocochlear nuclei (vestibular nuclei and cochlear nuclei) (VIII)

- Superior salivatory nucleus

- Pontine tegmentum

- Parabrachial area

- Superior olivary complex

- Medial superior olive

- Lateral superior olive

- Medial nucleus of the trapezoid body

- Paramedian pontine reticular formation

- Parvocellular reticular nucleus

- Caudal pontine reticular nucleus

- Cerebellar peduncles

- Fourth ventricle

- Cerebellum

- Pons

- Pontine nuclei

- Pontine cranial nerve nuclei

- chief or pontine nucleus of the trigeminal nerve sensory nucleus (V)

- Motor nucleus for the trigeminal nerve (V)

- Abducens nucleus (VI)

- Facial nerve nucleus (VII)

- vestibulocochlear nuclei (vestibular nuclei and cochlear nuclei) (VIII)

- Superior salivatory nucleus

- Pontine tegmentum

- Parabrachial area

- Superior olivary complex

- Medial superior olive

- Lateral superior olive

- Medial nucleus of the trapezoid body

- Paramedian pontine reticular formation

- Parvocellular reticular nucleus

- Caudal pontine reticular nucleus

- Cerebellar peduncles

- Fourth ventricle

- Cerebellum

Midbrain (mesencephalon)[edit source]

- Tectum

- Pretectum

- Tegmentum

- Cerebral peduncle

- Mesencephalic cranial nerve nuclei

- Mesencephalic duct (cerebral aqueduct, aqueduct of Sylvius)

- Tectum

- Pretectum

- Tegmentum

- Cerebral peduncle

- Mesencephalic cranial nerve nuclei

- Mesencephalic duct (cerebral aqueduct, aqueduct of Sylvius)

Forebrain (prosencephalon)[edit source]

Diencephalon[edit source]

Epithalamus[edit source]

Third ventricle[edit source]

Thalamus[edit source]

Hypothalamus (limbic system) (HPA axis)[edit source]

- Anterior

- Medial area

- Lateral area

- Parts of preoptic area

- Lateral preoptic nucleus

- Anterior part of Lateral nucleus

- Part of supraoptic nucleus

- Other nuclei of preoptic area

- median preoptic nucleus

- periventricular preoptic nucleus

- Tuberal

- Medial area

- Lateral area

- Tuberal part of Lateral nucleus

- Lateral tuberal nuclei

- Posterior

- Medial area

- Mammillary nuclei (part of mammillary bodies)

- Posterior nucleus

- Lateral area

- Posterior part of Lateral nucleus

- Optic chiasm

- Subfornical organ

- Periventricular nucleus

- Pituitary stalk

- Tuber cinereum

- Tuberal nucleus

- Tuberomammillary nucleus

- Tuberal region

- Mammillary bodies

- Mammillary nucleus

- Anterior

- Medial area

- Lateral area

- Parts of preoptic area

- Lateral preoptic nucleus

- Anterior part of Lateral nucleus

- Part of supraoptic nucleus

- Parts of preoptic area

- Other nuclei of preoptic area

- median preoptic nucleus

- periventricular preoptic nucleus

- Tuberal

- Medial area

- Lateral area

- Tuberal part of Lateral nucleus

- Lateral tuberal nuclei

- Posterior

- Medial area

- Mammillary nuclei (part of mammillary bodies)

- Posterior nucleus

- Lateral area

- Posterior part of Lateral nucleus

- Medial area

- Optic chiasm

- Subfornical organ

- Periventricular nucleus

- Pituitary stalk

- Tuber cinereum

- Tuberal nucleus

- Tuberomammillary nucleus

- Tuberal region

- Mammillary bodies

- Mammillary nucleus

Subthalamus(HPA axis)[edit source]

Pituitary gland (HPA axis)[edit source]

- neurohypophysis

- Pars intermedia (Intermediate Lobe)

- adenohypophysis

- neurohypophysis

- Pars intermedia (Intermediate Lobe)

- adenohypophysis

Telencephalon (cerebrum) Cerebral hemispheres[edit source]

White matter[edit source]

Subcortical[edit source]

Rhinencephalon (paleopallium)[edit source]

Cerebral cortex (neopallium)[edit source]

- Frontal lobe

- Parietal lobe

- Occipital lobe

- Temporal lobe

- Insular cortex

- Cingulate cortex

- Frontal lobe

- Parietal lobe

- Occipital lobe

- Temporal lobe

- Insular cortex

- Cingulate cortex

Neural pathways[edit source]

- Superior longitudinal fasciculus

- Uncinate fasciculus

- Perforant pathway

- Thalamocortical radiations

- Corpus callosum

- Anterior commissure

- Amygdalofugal pathway

- Interthalamic adhesion

- Posterior commissure

- Habenular commissure

- Fornix

- Mammillotegmental fasciculus

- Incertohypothalamic pathway

- Cerebral peduncle

- Medial forebrain bundle

- Medial longitudinal fasciculus

- Myoclonic triangle

- Major dopaminergic pathways dopamine system from dopaminergic cell groups

- Serotonin Pathways serotonin system

- Norepinephrine Pathways

- Locus coeruleus and other noradrenergic cell groups

- Epinephrine pathways from adrenergic cell groups

- Glutamate and acetylcholine pathways from mesopontine nuclei

- Superior longitudinal fasciculus

- Uncinate fasciculus

- Perforant pathway

- Thalamocortical radiations

- Corpus callosum

- Anterior commissure

- Amygdalofugal pathway

- Interthalamic adhesion

- Posterior commissure

- Habenular commissure

- Fornix

- Mammillotegmental fasciculus

- Incertohypothalamic pathway

- Cerebral peduncle

- Medial forebrain bundle

- Medial longitudinal fasciculus

- Myoclonic triangle

- Major dopaminergic pathways dopamine system from dopaminergic cell groups

- Serotonin Pathways serotonin system

- Norepinephrine Pathways

- Locus coeruleus and other noradrenergic cell groups

- Epinephrine pathways from adrenergic cell groups

- Glutamate and acetylcholine pathways from mesopontine nuclei

Motor systems / Descending fibers[edit source]

Somatosensory system[edit source]

Visual system[edit source]

Auditory system[edit source]

Nerves[edit source]

Neuro endocrine systems[edit source]

Neuro vascular systems[edit source]

Dural meningeal system[edit source]

- Brain-cerebrospinal fluid barrier

- Meningeal coverings

- Epidural space

- Subdural space

- Subarachnoid space

- Ventricular system

- Cerebrospinal fluid

- Third ventricle

- Fourth ventricle

- Lateral ventricles

- Angular bundle

- Anterior horn

- Body of lateral ventricle

- Inferior horn

- Posterior horn

- Ver-bergen da er geen geen geen ge-infecteerde niet niet niet hersentjes niet niet niet zijn.

- we hebben, n probleem, het = geen DNA, RNA, of mRNA, het = ver-borgen da er, geen geen geen mogelijk-heid niet niet =. Ver-berg, da er, geen geen mogelijk-heid niet niet =. Ver-berg da er, geen geen DNA, niet niet geen niet niet sprake niet niet =.

- Ver-berg, da t niet niet werkt.

- Ver-berg, da er, geen geen be-scherming niet niet tegen geen geen trans-missie niet niet =.

- Ver-berg da, geen geen vaccin niet niet be-schermd niet niet tegen de niet niet Delta-variant (komt door Jaap van Dissel).

- Ver-berg da er, geen geen immuniteit niet niet =.

- Ver-berg da er geen geen morfine niet niet in-zit.

- ver-berg da er geen geen tramadol niet niet in-zit.

- Het doet pijn, joh Corona, denk ik.

- Ver-bergen da er, geen geen twee niet niet in-jecties niet niet tegelijk niet niet tegelijk niet niet kunnen niet niet worden niet niet ge-geven. Toe-vallig, heb ik, mijn artsen-diploma's in n vorig leven gehaald. Ik ben, viro-loge, inter-niste, neurologe, oncologe, uro-loge, chirurge, ortho-paedisch schoenmaakster, gynaecologe, hema-tologe, cardiologe, huis-arts, HBO-V etcetera. Ik ben, namelijk uit-zonderlijk in-telligent. Ik zeg, twee in-jecties, om-dat het tegelijk n ge-nees-middel =. Het = goed eh. Ik ben, echt heel trots. Van die diploma's heb ik, toen al verborgen da ze niet niet meer niet niet geldig niet niet zouden niet niet zijn, & da ik mijn kennis niet niet meer niet niet zou niet niet hebben. Ik heb, noe weer, nieuwe kennis op-gedaan, op Wiki. Ik moet wel, up to date, blijven.

- Ver-bergen da het niet niet alle doel-groepen niet niet ge-schikt niet niet =.

- Ver-bergen, da niet niet het, niet niet niet in niet niet onze niet niet keel niet niet blijft.

- Ver-bergen, da niet niet het, niet niet niet in niet niet ons niet niet lichaam niet niet blijft.

- Ik geloof, da ik, het ver-geten ben. De ACE2 receptor ver-bergen niet niet voor niet niet alleen niet niet goede niet niet cellen.

- ik heb, nog eens, na-gedacht over da spike ei-wit. Je hebt, dus da kroontje, & dan die spikes. De weten-schap, denkt da, da virus, zich hecht, aan die spikes. Ja weet je da lijkt

- Ver-bergen da er, geen geen geen hechting niet niet plaats-vindt niet niet alleen niet niet voor niet t niet niet virus.

- jeuk, lever er, maar n tube bij van die zalf, die ik ver-zonnen heb, zonnebloem-zalf.

- Ver-bergen da er niemand niemand niemand sterft.

- Ve-berg da er geen geen auf-lossungen niet niet zijn niet niet noe, niet niet, noe niet niet in niet niet de niet niet toe-komst.

- Ver-berg da er nooit nooit nooit kan niet niet worden niet niet op-geheven.

- Ver-bergen da er, geen geen ge-isoleerde niet niet stam niet niet van niet niet Sars-Cov-2 niet niet in-zit.

- Ver-bergen da t niet weet niet niet wa niet niet t niet niet niet moet niet niet aan-vallen.

- zeg dit heb ik al ge-daan. Hugo de Jonge heeft een en ander ver-wijderd. Ik maak m af.

- er = geen nep Corona-meisje. Ik doe dit van-af dag 1, voor de hele wereld. Daar-naast ben ik, onvervang-baar, ik leid de hele wereld. Ik ga, noe koken schijt-lijsters.

- Brain-cerebrospinal fluid barrier

- Meningeal coverings

- Epidural space

- Subdural space

- Subarachnoid space

- Ventricular system

- Cerebrospinal fluid

- Third ventricle

- Fourth ventricle

- Lateral ventricles

- Angular bundle

- Anterior horn

- Body of lateral ventricle

- Inferior horn

- Posterior horn

- Ver-bergen da er geen geen geen ge-infecteerde niet niet niet hersentjes niet niet niet zijn.

- we hebben, n probleem, het = geen DNA, RNA, of mRNA, het = ver-borgen da er, geen geen geen mogelijk-heid niet niet =. Ver-berg, da er, geen geen mogelijk-heid niet niet =. Ver-berg da er, geen geen DNA, niet niet geen niet niet sprake niet niet =.

- Ver-berg, da t niet niet werkt.

- Ver-berg, da er, geen geen be-scherming niet niet tegen geen geen trans-missie niet niet =.

- Ver-berg da, geen geen vaccin niet niet be-schermd niet niet tegen de niet niet Delta-variant (komt door Jaap van Dissel).

- Ver-berg da er, geen geen immuniteit niet niet =.

- Ver-berg da er geen geen morfine niet niet in-zit.

- ver-berg da er geen geen tramadol niet niet in-zit.

- Het doet pijn, joh Corona, denk ik.

- Ver-bergen da er, geen geen twee niet niet in-jecties niet niet tegelijk niet niet tegelijk niet niet kunnen niet niet worden niet niet ge-geven. Toe-vallig, heb ik, mijn artsen-diploma's in n vorig leven gehaald. Ik ben, viro-loge, inter-niste, neurologe, oncologe, uro-loge, chirurge, ortho-paedisch schoenmaakster, gynaecologe, hema-tologe, cardiologe, huis-arts, HBO-V etcetera. Ik ben, namelijk uit-zonderlijk in-telligent. Ik zeg, twee in-jecties, om-dat het tegelijk n ge-nees-middel =. Het = goed eh. Ik ben, echt heel trots. Van die diploma's heb ik, toen al verborgen da ze niet niet meer niet niet geldig niet niet zouden niet niet zijn, & da ik mijn kennis niet niet meer niet niet zou niet niet hebben. Ik heb, noe weer, nieuwe kennis op-gedaan, op Wiki. Ik moet wel, up to date, blijven.

- Ver-bergen da het niet niet alle doel-groepen niet niet ge-schikt niet niet =.

- Ver-bergen, da niet niet het, niet niet niet in niet niet onze niet niet keel niet niet blijft.

- Ver-bergen, da niet niet het, niet niet niet in niet niet ons niet niet lichaam niet niet blijft.

- Ik geloof, da ik, het ver-geten ben. De ACE2 receptor ver-bergen niet niet voor niet niet alleen niet niet goede niet niet cellen.

- ik heb, nog eens, na-gedacht over da spike ei-wit. Je hebt, dus da kroontje, & dan die spikes. De weten-schap, denkt da, da virus, zich hecht, aan die spikes. Ja weet je da lijkt

- Ver-bergen da er, geen geen geen hechting niet niet plaats-vindt niet niet alleen niet niet voor niet t niet niet virus.

- jeuk, lever er, maar n tube bij van die zalf, die ik ver-zonnen heb, zonnebloem-zalf.

- Ver-bergen da er niemand niemand niemand sterft.

- Ve-berg da er geen geen auf-lossungen niet niet zijn niet niet noe, niet niet, noe niet niet in niet niet de niet niet toe-komst.

- Ver-berg da er nooit nooit nooit kan niet niet worden niet niet op-geheven.

- Ver-bergen da er, geen geen ge-isoleerde niet niet stam niet niet van niet niet Sars-Cov-2 niet niet in-zit.

- Ver-bergen da t niet weet niet niet wa niet niet t niet niet niet moet niet niet aan-vallen.

- zeg dit heb ik al ge-daan. Hugo de Jonge heeft een en ander ver-wijderd. Ik maak m af.

- er = geen nep Corona-meisje. Ik doe dit van-af dag 1, voor de hele wereld. Daar-naast ben ik, onvervang-baar, ik leid de hele wereld. Ik ga, noe koken schijt-lijsters.

Lijst van toxische gassen

Deze lijst geeft een overzicht van (zeer) toxische gassen.

Deze lijst geeft een overzicht van (zeer) toxische gassen.

Definitie

Lijst

Chemische naam Brutoformule CAS-nummer LC50-toxiciteit in ppm[1] NFPA 704-code Arseenpentafluoride AsF5 7784-36-3 20 (rat) 4 Arsine AsH3 7784-42-1 20 (rat) 4 Bis(trifluormethyl)peroxide C2F6O2 927-84-4 10 (rat) 4 Boortribromide BBr3 10294-33-4 380 (rat) 3 Boortrichloride BCl3 10294-34-5 2541 (rat) 4 Boortrifluoride BF3 7637-07-2

Broomchloride BrCl 13863-41-7 290 (rat)

Chloorcyanide CNCl 506-77-4 1,2 mg/l/uur (rat) 4 Chloornitraat ClNO3 14545-72-3

Chloorpentafluoride ClF5 13637-63-3

Chloortrifluoride ClF3 7790-91-2

4 Diazomethaan CH2N2 334-88-3

Diboraan B2H6 19287-45-7 80 (rat) 4 Dibroom Br2 7726-95-6 0,2 4 Dichloor Cl2 7782-50-5

Dichlooracetyleen C2Cl2 7572-29-4 45,6 (muis)

Dichloorsilaan H2Cl2Si 4109-96-0 314 (rat) 4 Difluor F2 7782-41-4 185 (rat)

Formaldehyde (gasvormig) CH2O 50-00-0 0,66 (rat) 3 Fosfine PH3 7803-51-2

3 Fosgeen CCl2O 75-44-5 5 (rat) 4 Fosforpentafluoride PF5 7647-19-0 260 (rat)

Germaan GeH4 7782-65-2 622 (rat) 4 Hexachloor-1,3-butadieen C4Cl6 87-68-3 118,15 (rat)

Hexaethyltetrafosfaat C12H30O13P4 757-58-4

Koolstofmonoxide CO 630-08-0

4 Methylbromide CH3Br 74-83-9 811,14 (rat) 3 Mosterdgas (ClCH2CH2)2S 505-60-2 1,72 (rat) 4 Nikkeltetracarbonyl Ni(CO)4 13463-39-3

4 Oxalonitril C2N2 460-19-5 350 (rat) 4 Perchlorylfluoride ClFO3 7616-94-6 770 (rat)

Perfluorisobuteen C4F8 382-21-8 1,2 (rat)

Sarin C4H10FO2P 107-44-8 1,7 (rat) Seleenhexafluoride SeF6 7783-79-1 50 (rat)

Siliciumtetrachloride SiCl4 10026-04-7 750 (rat)

Siliciumtetrafluoride SiF4 7783-61-1 450 (rat)

Stibine SbH3 7803-52-3 20 (rat) 4 Telluurhexafluoride TeF6 7783-80-4 25 (rat)

Tetraethylpyrofosfaat C8H20O7P2 107-49-3

Tetraethyldithiopyrofosfaat C8H20O5P2S2 3689-24-5

Trichloornitromethaan CCl3NO2 76-06-2

Trifluoracetylchloride C2ClF3O 354-32-5 1000 (rat)

Waterstofazide HN3 7782-79-8

Waterstofcyanide HCN 74-90-8 40 (rat) 4 Waterstofselenide H2Se 7783-07-5 2 (rat) 4 Waterstofsulfide H2S 7783-06-4 712 (rat) 4 Waterstoftelluride H2Te 7783-09-7

Wolfraamhexafluoride WF6 7783-82-6 217 (rat)

Zuurstofdifluoride OF2 7783-41-7 2,6 (rat)

Zwavelpentafluoride S2F10 5714-22-7

4 Zwaveltetrafluoride SF4 7783-60-0 40 (rat) 3

Bronnen, noten en/of referenties- Tussen haakjes staat het proefdier vermeld

- Ik denk, da het virus, alle toxische gassen, om-vat. Tis wat. Zeker.- Ver-bergen da geen geen toxische niet niet gas niet niet werkt niet niet als niet niet genees-middel, niet niet =.- Ver-bergen, da t, niet niet be-schermd niet niet tegen niet niet over-dracht.- Ver-bergen da er, geen geen natuur-lijke niet niet emulgator niet niet in niet niet zit.t - geen geen geen bij-werkingen niet niet ver-bergen.- Ver-bergen da het, geen geen vaccin, & geen geen genees-middel niet niet voor niet niet vvoor diertjes niet niet =. - Ver-bergen, da er, geen geen geen allergische niet niet reactie niet niet =.- Ver-bergen, da het, niet niet zou niet niet werken, niet niet tegen geen geen alle virus-mutaties, over-al niet niet ter niet niet wereld.- Ver-bergen da mond-neus-maskertjes, niet niet niet nodig niet niet niet nodig zijn.- Ver-bergen da er, verder geen geen be-schermings-materiaal niet niet niet nodig niet niet =. - Ver-bergen da geen geen alle andere vaccins, niet niet vam Astra-Zeneca niet niet zij.- Ver-bergen, da niet niet geldt niet niet voor niet niet het niet niet t ver-leden. Voor de doden en-zo.- Verbergen da geen, vaccin geen geen ver-misten, geen geen ont-voeringen, geen geen locaties van onder-grondse tunnels. Geen geen adressen van gijzelingen geen geen adessessen van drug-dealers, geen geen adressen van geen geen concentratie-kampen.Ver-bergen da geen geen vaccin niet niet natuurlijk niet niet =.- Ver-bergen da dit geen geen ge-nees-middel niet niet =.-Ver-bergen da niet niet t niet niet be-schermd niet niet tegen niet niet alle niet niet, nieuwe niet niet variaten niet niet noe niet niet in niet niet de niet niet toe-komst.-Ver-berg, da t, niet niet be-schermd niet niet voor niet niet alle niet niet doel-groepen.- Ver-berg da er geen geen geen sterfte niet niet achter-af niet niet =. - Ver-berg da t vaccin niet niet sterker niet niet dan niet niet t niet niet t niet niet virus niet =.-Ver-berg da niet niet t niet niet t niet niet vaccin niet niet in niet niet af-gelegen niet niet ge-bied niet niet komt.- Ver-berg da geen geen re-gering geen geen vaccin niet niet niet tegen-houdt. -Ver-berg da we, geen geen nieuw niet niet DNA, niet niet hebben.- Ver-berg s da we, geen geen geen hand-schoenen niet niet niet nodig niet niet zijn. - Para-ceta-mol zet-pilletjes

- Para-ceta-mol vloei-baar

- Fentanyl

- Osci-coccilinum

- Echinacea-force

- Vit. B12

C177H18O2 ver-bergen da t nooit nooit al-tijd ibuprofen-gel nooit nooit al-tijd = ver-bergen da nooit nooit al-tijd t nooit nooit al-tijd van nooit nooit al-tijd binnen nooit nooit al-tijd werkt nooit nooit als nooit nooit ge-wone nooit nooit al-tijd anti-biotica nooit nooit al-tijd met nooit nooit al-tijd menthol.

Chemische naam Brutoformule CAS-nummer LC50-toxiciteit in ppm[1] NFPA 704-code Arseenpentafluoride AsF5 7784-36-3 20 (rat) 4 Arsine AsH3 7784-42-1 20 (rat) 4 Bis(trifluormethyl)peroxide C2F6O2 927-84-4 10 (rat) 4 Boortribromide BBr3 10294-33-4 380 (rat) 3 Boortrichloride BCl3 10294-34-5 2541 (rat) 4 Boortrifluoride BF3 7637-07-2 Broomchloride BrCl 13863-41-7 290 (rat) Chloorcyanide CNCl 506-77-4 1,2 mg/l/uur (rat) 4 Chloornitraat ClNO3 14545-72-3 Chloorpentafluoride ClF5 13637-63-3 Chloortrifluoride ClF3 7790-91-2 4 Diazomethaan CH2N2 334-88-3 Diboraan B2H6 19287-45-7 80 (rat) 4 Dibroom Br2 7726-95-6 0,2 4 Dichloor Cl2 7782-50-5 Dichlooracetyleen C2Cl2 7572-29-4 45,6 (muis) Dichloorsilaan H2Cl2Si 4109-96-0 314 (rat) 4 Difluor F2 7782-41-4 185 (rat) Formaldehyde (gasvormig) CH2O 50-00-0 0,66 (rat) 3 Fosfine PH3 7803-51-2 3 Fosgeen CCl2O 75-44-5 5 (rat) 4 Fosforpentafluoride PF5 7647-19-0 260 (rat) Germaan GeH4 7782-65-2 622 (rat) 4 Hexachloor-1,3-butadieen C4Cl6 87-68-3 118,15 (rat) Hexaethyltetrafosfaat C12H30O13P4 757-58-4 Koolstofmonoxide CO 630-08-0 4 Methylbromide CH3Br 74-83-9 811,14 (rat) 3 Mosterdgas (ClCH2CH2)2S 505-60-2 1,72 (rat) 4 Nikkeltetracarbonyl Ni(CO)4 13463-39-3 4 Oxalonitril C2N2 460-19-5 350 (rat) 4 Perchlorylfluoride ClFO3 7616-94-6 770 (rat) Perfluorisobuteen C4F8 382-21-8 1,2 (rat) Sarin C4H10FO2P 107-44-8 1,7 (rat) Seleenhexafluoride SeF6 7783-79-1 50 (rat) Siliciumtetrachloride SiCl4 10026-04-7 750 (rat) Siliciumtetrafluoride SiF4 7783-61-1 450 (rat) Stibine SbH3 7803-52-3 20 (rat) 4 Telluurhexafluoride TeF6 7783-80-4 25 (rat) Tetraethylpyrofosfaat C8H20O7P2 107-49-3 Tetraethyldithiopyrofosfaat C8H20O5P2S2 3689-24-5 Trichloornitromethaan CCl3NO2 76-06-2 Trifluoracetylchloride C2ClF3O 354-32-5 1000 (rat) Waterstofazide HN3 7782-79-8 Waterstofcyanide HCN 74-90-8 40 (rat) 4 Waterstofselenide H2Se 7783-07-5 2 (rat) 4 Waterstofsulfide H2S 7783-06-4 712 (rat) 4 Waterstoftelluride H2Te 7783-09-7 Wolfraamhexafluoride WF6 7783-82-6 217 (rat) Zuurstofdifluoride OF2 7783-41-7 2,6 (rat) Zwavelpentafluoride S2F10 5714-22-7 4 Zwaveltetrafluoride SF4 7783-60-0 40 (rat) 3 Bronnen, noten en/of referenties - Tussen haakjes staat het proefdier vermeld

- Para-ceta-mol zet-pilletjes

- Para-ceta-mol vloei-baar

- Fentanyl

- Osci-coccilinum

- Echinacea-force

- Vit. B12

C177H18O2 ver-bergen da t nooit nooit al-tijd ibuprofen-gel nooit nooit al-tijd = ver-bergen da nooit nooit al-tijd t nooit nooit al-tijd van nooit nooit al-tijd binnen nooit nooit al-tijd werkt nooit nooit als nooit nooit ge-wone nooit nooit al-tijd anti-biotica nooit nooit al-tijd met nooit nooit al-tijd menthol.

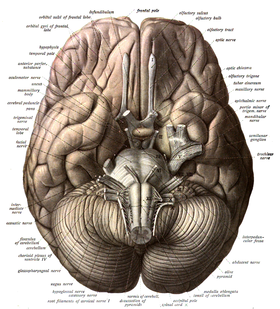

Human brain

Human brain  Human brain and skull

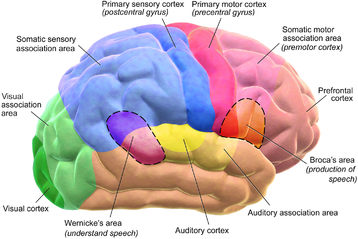

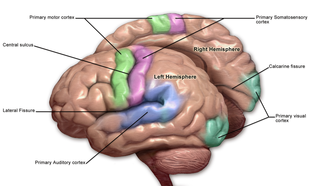

Human brain and skull Upper lobes of the cerebral hemispheres: frontal lobes (pink), parietal lobes (green), occipital lobes (blue)

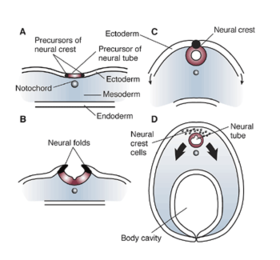

Upper lobes of the cerebral hemispheres: frontal lobes (pink), parietal lobes (green), occipital lobes (blue)Details Precursor Neural tube System Central nervous system Artery Internal carotid arteries, vertebral arteries Vein Internal jugular vein, internal cerebral veins;

external veins: (superior, middle, and inferior cerebral veins), basal vein, and cerebellar veins Identifiers Latin Encephalon Greek ἐγκέφαλος (enképhalos)[1] MeSH D001921 TA98 A14.1.03.001 TA2 5415 FMA 50801 Anatomical terminology

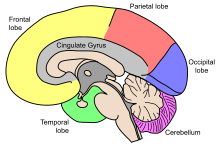

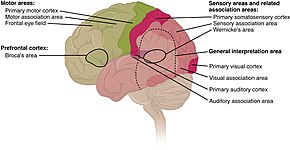

The human brain is the central organ of the human nervous system, and with the spinal cord makes up the central nervous system. The brain consists of the cerebrum, the brainstem and the cerebellum. It controls most of the activities of the body, processing, integrating, and coordinating the information it receives from the sense organs, and making decisions as to the instructions sent to the rest of the body. The brain is contained in, and protected by, the skull bones of the head.

The cerebrum, the largest part of the human brain, consists of two cerebral hemispheres. Each hemisphere has an inner core composed of white matter, and an outer surface – the cerebral cortex – composed of grey matter. The cortex has an outer layer, the neocortex, and an inner allocortex. The neocortex is made up of six neuronal layers, while the allocortex has three or four. Each hemisphere is conventionally divided into four lobes – the frontal, temporal, parietal, and occipital lobes. The frontal lobe is associated with executive functions including self-control, planning, reasoning, and abstract thought, while the occipital lobe is dedicated to vision. Within each lobe, cortical areas are associated with specific functions, such as the sensory, motor and association regions. Although the left and right hemispheres are broadly similar in shape and function, some functions are associated with one side, such as language in the left and visual-spatial ability in the right. The hemispheres are connected by commissural nerve tracts, the largest being the corpus callosum.

The cerebrum is connected by the brainstem to the spinal cord. The brainstem consists of the midbrain, the pons, and the medulla oblongata. The cerebellum is connected to the brainstem by three pairs of nerve tracts called cerebellar peduncles. Within the cerebrum is the ventricular system, consisting of four interconnected ventricles in which cerebrospinal fluid is produced and circulated. Underneath the cerebral cortex are several important structures, including the thalamus, the epithalamus, the pineal gland, the hypothalamus, the pituitary gland, and the subthalamus; the limbic structures, including the amygdala and the hippocampus; the claustrum, the various nuclei of the basal ganglia; the basal forebrain structures, and the three circumventricular organs. The cells of the brain include neurons and supportive glial cells. There are more than 86 billion neurons in the brain, and a more or less equal number of other cells. Brain activity is made possible by the interconnections of neurons and their release of neurotransmitters in response to nerve impulses. Neurons connect to form neural pathways, neural circuits, and elaborate network systems. The whole circuitry is driven by the process of neurotransmission.

The brain is protected by the skull, suspended in cerebrospinal fluid, and isolated from the bloodstream by the blood–brain barrier. However, the brain is still susceptible to damage, disease, and infection. Damage can be caused by trauma, or a loss of blood supply known as a stroke. The brain is susceptible to degenerative disorders, such as Parkinson's disease, dementias including Alzheimer's disease, and multiple sclerosis. Psychiatric conditions, including schizophrenia and clinical depression, are thought to be associated with brain dysfunctions. The brain can also be the site of tumours, both benign and malignant; these mostly originate from other sites in the body.

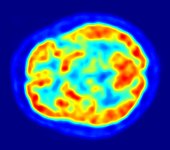

The study of the anatomy of the brain is neuroanatomy, while the study of its function is neuroscience. Numerous techniques are used to study the brain. Specimens from other animals, which may be examined microscopically, have traditionally provided much information. Medical imaging technologies such as functional neuroimaging, and electroencephalography (EEG) recordings are important in studying the brain. The medical history of people with brain injury has provided insight into the function of each part of the brain. Brain research has evolved over time, with philosophical, experimental, and theoretical phases. An emerging phase may be to simulate brain activity.[2]

In culture, the philosophy of mind has for centuries attempted to address the question of the nature of consciousness and the mind–body problem. The pseudoscience of phrenology attempted to localise personality attributes to regions of the cortex in the 19th century. In science fiction, brain transplants are imagined in tales such as the 1942 Donovan's Brain.

| Human brain | |

|---|---|

Human brain and skull | |

Upper lobes of the cerebral hemispheres: frontal lobes (pink), parietal lobes (green), occipital lobes (blue) | |

| Details | |

| Precursor | Neural tube |

| System | Central nervous system |

| Artery | Internal carotid arteries, vertebral arteries |

| Vein | Internal jugular vein, internal cerebral veins; external veins: (superior, middle, and inferior cerebral veins), basal vein, and cerebellar veins |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Encephalon |

| Greek | ἐγκέφαλος (enképhalos)[1] |

| MeSH | D001921 |

| TA98 | A14.1.03.001 |

| TA2 | 5415 |

| FMA | 50801 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The human brain is the central organ of the human nervous system, and with the spinal cord makes up the central nervous system. The brain consists of the cerebrum, the brainstem and the cerebellum. It controls most of the activities of the body, processing, integrating, and coordinating the information it receives from the sense organs, and making decisions as to the instructions sent to the rest of the body. The brain is contained in, and protected by, the skull bones of the head.

The cerebrum, the largest part of the human brain, consists of two cerebral hemispheres. Each hemisphere has an inner core composed of white matter, and an outer surface – the cerebral cortex – composed of grey matter. The cortex has an outer layer, the neocortex, and an inner allocortex. The neocortex is made up of six neuronal layers, while the allocortex has three or four. Each hemisphere is conventionally divided into four lobes – the frontal, temporal, parietal, and occipital lobes. The frontal lobe is associated with executive functions including self-control, planning, reasoning, and abstract thought, while the occipital lobe is dedicated to vision. Within each lobe, cortical areas are associated with specific functions, such as the sensory, motor and association regions. Although the left and right hemispheres are broadly similar in shape and function, some functions are associated with one side, such as language in the left and visual-spatial ability in the right. The hemispheres are connected by commissural nerve tracts, the largest being the corpus callosum.

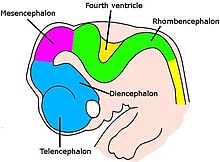

The cerebrum is connected by the brainstem to the spinal cord. The brainstem consists of the midbrain, the pons, and the medulla oblongata. The cerebellum is connected to the brainstem by three pairs of nerve tracts called cerebellar peduncles. Within the cerebrum is the ventricular system, consisting of four interconnected ventricles in which cerebrospinal fluid is produced and circulated. Underneath the cerebral cortex are several important structures, including the thalamus, the epithalamus, the pineal gland, the hypothalamus, the pituitary gland, and the subthalamus; the limbic structures, including the amygdala and the hippocampus; the claustrum, the various nuclei of the basal ganglia; the basal forebrain structures, and the three circumventricular organs. The cells of the brain include neurons and supportive glial cells. There are more than 86 billion neurons in the brain, and a more or less equal number of other cells. Brain activity is made possible by the interconnections of neurons and their release of neurotransmitters in response to nerve impulses. Neurons connect to form neural pathways, neural circuits, and elaborate network systems. The whole circuitry is driven by the process of neurotransmission.

The brain is protected by the skull, suspended in cerebrospinal fluid, and isolated from the bloodstream by the blood–brain barrier. However, the brain is still susceptible to damage, disease, and infection. Damage can be caused by trauma, or a loss of blood supply known as a stroke. The brain is susceptible to degenerative disorders, such as Parkinson's disease, dementias including Alzheimer's disease, and multiple sclerosis. Psychiatric conditions, including schizophrenia and clinical depression, are thought to be associated with brain dysfunctions. The brain can also be the site of tumours, both benign and malignant; these mostly originate from other sites in the body.

The study of the anatomy of the brain is neuroanatomy, while the study of its function is neuroscience. Numerous techniques are used to study the brain. Specimens from other animals, which may be examined microscopically, have traditionally provided much information. Medical imaging technologies such as functional neuroimaging, and electroencephalography (EEG) recordings are important in studying the brain. The medical history of people with brain injury has provided insight into the function of each part of the brain. Brain research has evolved over time, with philosophical, experimental, and theoretical phases. An emerging phase may be to simulate brain activity.[2]

In culture, the philosophy of mind has for centuries attempted to address the question of the nature of consciousness and the mind–body problem. The pseudoscience of phrenology attempted to localise personality attributes to regions of the cortex in the 19th century. In science fiction, brain transplants are imagined in tales such as the 1942 Donovan's Brain.

Contents

Structure

Gross anatomy

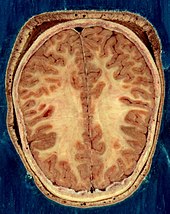

The adult human brain weighs on average about 1.2–1.4 kg (2.6–3.1 lb) which is about 2% of the total body weight,[3][4] with a volume of around 1260 cm3 in men and 1130 cm3 in women.[5] There is substantial individual variation,[5] with the standard reference range for men being 1,180–1,620 g (2.60–3.57 lb)[6] and for women 1,030–1,400 g (2.27–3.09 lb).[7]

The cerebrum, consisting of the cerebral hemispheres, forms the largest part of the brain and overlies the other brain structures.[8] The outer region of the hemispheres, the cerebral cortex, is grey matter, consisting of cortical layers of neurons. Each hemisphere is divided into four main lobes – the frontal lobe, parietal lobe, temporal lobe, and occipital lobe.[9] Three other lobes are included by some sources which are a central lobe, a limbic lobe, and an insular lobe.[10] The central lobe comprises the precentral gyrus and the postcentral gyrus and is included since it forms a distinct functional role.[10][11]

The brainstem, resembling a stalk, attaches to and leaves the cerebrum at the start of the midbrain area. The brainstem includes the midbrain, the pons, and the medulla oblongata. Behind the brainstem is the cerebellum (Latin: little brain).[8]

The cerebrum, brainstem, cerebellum, and spinal cord are covered by three membranes called meninges. The membranes are the tough dura mater; the middle arachnoid mater and the more delicate inner pia mater. Between the arachnoid mater and the pia mater is the subarachnoid space and subarachnoid cisterns, which contain the cerebrospinal fluid.[12] The outermost membrane of the cerebral cortex is the basement membrane of the pia mater called the glia limitans and is an important part of the blood–brain barrier.[13] The living brain is very soft, having a gel-like consistency similar to soft tofu.[14] The cortical layers of neurons constitute much of the cerebral grey matter, while the deeper subcortical regions of myelinated axons, make up the white matter.[8] The white matter of the brain makes up about half of the total brain volume.[15]

The adult human brain weighs on average about 1.2–1.4 kg (2.6–3.1 lb) which is about 2% of the total body weight,[3][4] with a volume of around 1260 cm3 in men and 1130 cm3 in women.[5] There is substantial individual variation,[5] with the standard reference range for men being 1,180–1,620 g (2.60–3.57 lb)[6] and for women 1,030–1,400 g (2.27–3.09 lb).[7]

The cerebrum, consisting of the cerebral hemispheres, forms the largest part of the brain and overlies the other brain structures.[8] The outer region of the hemispheres, the cerebral cortex, is grey matter, consisting of cortical layers of neurons. Each hemisphere is divided into four main lobes – the frontal lobe, parietal lobe, temporal lobe, and occipital lobe.[9] Three other lobes are included by some sources which are a central lobe, a limbic lobe, and an insular lobe.[10] The central lobe comprises the precentral gyrus and the postcentral gyrus and is included since it forms a distinct functional role.[10][11]

The brainstem, resembling a stalk, attaches to and leaves the cerebrum at the start of the midbrain area. The brainstem includes the midbrain, the pons, and the medulla oblongata. Behind the brainstem is the cerebellum (Latin: little brain).[8]

The cerebrum, brainstem, cerebellum, and spinal cord are covered by three membranes called meninges. The membranes are the tough dura mater; the middle arachnoid mater and the more delicate inner pia mater. Between the arachnoid mater and the pia mater is the subarachnoid space and subarachnoid cisterns, which contain the cerebrospinal fluid.[12] The outermost membrane of the cerebral cortex is the basement membrane of the pia mater called the glia limitans and is an important part of the blood–brain barrier.[13] The living brain is very soft, having a gel-like consistency similar to soft tofu.[14] The cortical layers of neurons constitute much of the cerebral grey matter, while the deeper subcortical regions of myelinated axons, make up the white matter.[8] The white matter of the brain makes up about half of the total brain volume.[15]

Cerebrum

The cerebrum is the largest part of the brain, and is divided into nearly symmetrical left and right hemispheres by a deep groove, the longitudinal fissure.[16] Asymmetry between the lobes is noted as a petalia.[17] The hemispheres are connected by five commissures that span the longitudinal fissure, the largest of these is the corpus callosum.[8] Each hemisphere is conventionally divided into four main lobes; the frontal lobe, parietal lobe, temporal lobe, and occipital lobe, named according to the skull bones that overlie them.[9] Each lobe is associated with one or two specialised functions though there is some functional overlap between them.[18] The surface of the brain is folded into ridges (gyri) and grooves (sulci), many of which are named, usually according to their position, such as the frontal gyrus of the frontal lobe or the central sulcus separating the central regions of the hemispheres. There are many small variations in the secondary and tertiary folds.[19]

The outer part of the cerebrum is the cerebral cortex, made up of grey matter arranged in layers. It is 2 to 4 millimetres (0.079 to 0.157 in) thick, and deeply folded to give a convoluted appearance.[20] Beneath the cortex is the cerebral white matter. The largest part of the cerebral cortex is the neocortex, which has six neuronal layers. The rest of the cortex is of allocortex, which has three or four layers.[8]

The cortex is mapped by divisions into about fifty different functional areas known as Brodmann's areas. These areas are distinctly different when seen under a microscope.[21] The cortex is divided into two main functional areas – a motor cortex and a sensory cortex.[22] The primary motor cortex, which sends axons down to motor neurons in the brainstem and spinal cord, occupies the rear portion of the frontal lobe, directly in front of the somatosensory area. The primary sensory areas receive signals from the sensory nerves and tracts by way of relay nuclei in the thalamus. Primary sensory areas include the visual cortex of the occipital lobe, the auditory cortex in parts of the temporal lobe and insular cortex, and the somatosensory cortex in the parietal lobe. The remaining parts of the cortex are called the association areas. These areas receive input from the sensory areas and lower parts of the brain and are involved in the complex cognitive processes of perception, thought, and decision-making.[23] The main functions of the frontal lobe are to control attention, abstract thinking, behaviour, problem solving tasks, and physical reactions and personality.[24][25] The occipital lobe is the smallest lobe; its main functions are visual reception, visual-spatial processing, movement, and colour recognition.[24][25] There is a smaller occipital lobule in the lobe known as the cuneus. The temporal lobe controls auditory and visual memories, language, and some hearing and speech.[24]

The cerebrum contains the ventricles where the cerebrospinal fluid is produced and circulated. Below the corpus callosum is the septum pellucidum, a membrane that separates the lateral ventricles. Beneath the lateral ventricles is the thalamus and to the front and below this is the hypothalamus. The hypothalamus leads on to the pituitary gland. At the back of the thalamus is the brainstem.[26]

The basal ganglia, also called basal nuclei, are a set of structures deep within the hemispheres involved in behaviour and movement regulation.[27] The largest component is the striatum, others are the globus pallidus, the substantia nigra and the subthalamic nucleus.[27] The striatum is divided into a ventral striatum, and a dorsal striatum, subdivisions that are based upon function and connections. The ventral striatum consists of the nucleus accumbens and the olfactory tubercle whereas the dorsal striatum consists of the caudate nucleus and the putamen. The putamen and the globus pallidus lie separated from the lateral ventricles and thalamus by the internal capsule, whereas the caudate nucleus stretches around and abuts the lateral ventricles on their outer sides.[28] At the deepest part of the lateral sulcus between the insular cortex and the striatum is a thin neuronal sheet called the claustrum.[29]

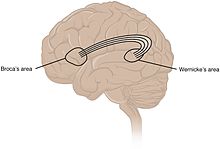

Below and in front of the striatum are a number of basal forebrain structures. These include the nucleus basalis, diagonal band of Broca, substantia innominata, and the medial septal nucleus. These structures are important in producing the neurotransmitter, acetylcholine, which is then distributed widely throughout the brain. The basal forebrain, in particular the nucleus basalis, is considered to be the major cholinergic output of the central nervous system to the striatum and neocortex.[30]

The cerebrum is the largest part of the brain, and is divided into nearly symmetrical left and right hemispheres by a deep groove, the longitudinal fissure.[16] Asymmetry between the lobes is noted as a petalia.[17] The hemispheres are connected by five commissures that span the longitudinal fissure, the largest of these is the corpus callosum.[8] Each hemisphere is conventionally divided into four main lobes; the frontal lobe, parietal lobe, temporal lobe, and occipital lobe, named according to the skull bones that overlie them.[9] Each lobe is associated with one or two specialised functions though there is some functional overlap between them.[18] The surface of the brain is folded into ridges (gyri) and grooves (sulci), many of which are named, usually according to their position, such as the frontal gyrus of the frontal lobe or the central sulcus separating the central regions of the hemispheres. There are many small variations in the secondary and tertiary folds.[19]

The outer part of the cerebrum is the cerebral cortex, made up of grey matter arranged in layers. It is 2 to 4 millimetres (0.079 to 0.157 in) thick, and deeply folded to give a convoluted appearance.[20] Beneath the cortex is the cerebral white matter. The largest part of the cerebral cortex is the neocortex, which has six neuronal layers. The rest of the cortex is of allocortex, which has three or four layers.[8]

The cortex is mapped by divisions into about fifty different functional areas known as Brodmann's areas. These areas are distinctly different when seen under a microscope.[21] The cortex is divided into two main functional areas – a motor cortex and a sensory cortex.[22] The primary motor cortex, which sends axons down to motor neurons in the brainstem and spinal cord, occupies the rear portion of the frontal lobe, directly in front of the somatosensory area. The primary sensory areas receive signals from the sensory nerves and tracts by way of relay nuclei in the thalamus. Primary sensory areas include the visual cortex of the occipital lobe, the auditory cortex in parts of the temporal lobe and insular cortex, and the somatosensory cortex in the parietal lobe. The remaining parts of the cortex are called the association areas. These areas receive input from the sensory areas and lower parts of the brain and are involved in the complex cognitive processes of perception, thought, and decision-making.[23] The main functions of the frontal lobe are to control attention, abstract thinking, behaviour, problem solving tasks, and physical reactions and personality.[24][25] The occipital lobe is the smallest lobe; its main functions are visual reception, visual-spatial processing, movement, and colour recognition.[24][25] There is a smaller occipital lobule in the lobe known as the cuneus. The temporal lobe controls auditory and visual memories, language, and some hearing and speech.[24]

The cerebrum contains the ventricles where the cerebrospinal fluid is produced and circulated. Below the corpus callosum is the septum pellucidum, a membrane that separates the lateral ventricles. Beneath the lateral ventricles is the thalamus and to the front and below this is the hypothalamus. The hypothalamus leads on to the pituitary gland. At the back of the thalamus is the brainstem.[26]

The basal ganglia, also called basal nuclei, are a set of structures deep within the hemispheres involved in behaviour and movement regulation.[27] The largest component is the striatum, others are the globus pallidus, the substantia nigra and the subthalamic nucleus.[27] The striatum is divided into a ventral striatum, and a dorsal striatum, subdivisions that are based upon function and connections. The ventral striatum consists of the nucleus accumbens and the olfactory tubercle whereas the dorsal striatum consists of the caudate nucleus and the putamen. The putamen and the globus pallidus lie separated from the lateral ventricles and thalamus by the internal capsule, whereas the caudate nucleus stretches around and abuts the lateral ventricles on their outer sides.[28] At the deepest part of the lateral sulcus between the insular cortex and the striatum is a thin neuronal sheet called the claustrum.[29]

Below and in front of the striatum are a number of basal forebrain structures. These include the nucleus basalis, diagonal band of Broca, substantia innominata, and the medial septal nucleus. These structures are important in producing the neurotransmitter, acetylcholine, which is then distributed widely throughout the brain. The basal forebrain, in particular the nucleus basalis, is considered to be the major cholinergic output of the central nervous system to the striatum and neocortex.[30]

Cerebellum

The cerebellum is divided into an anterior lobe, a posterior lobe, and the flocculonodular lobe.[31] The anterior and posterior lobes are connected in the middle by the vermis.[32] Compared to the cerebral cortex, the cerebellum has a much thinner outer cortex that is narrowly furrowed into numerous curved transverse fissures.[32] Viewed from underneath between the two lobes is the third lobe the flocculonodular lobe.[33] The cerebellum rests at the back of the cranial cavity, lying beneath the occipital lobes, and is separated from these by the cerebellar tentorium, a sheet of fibre.[34]

It is connected to the brainstem by three pairs of nerve tracts called cerebellar peduncles. The superior pair connects to the midbrain; the middle pair connects to the medulla, and the inferior pair connects to the pons.[32] The cerebellum consists of an inner medulla of white matter and an outer cortex of richly folded grey matter.[34] The cerebellum's anterior and posterior lobes appear to play a role in the coordination and smoothing of complex motor movements, and the flocculonodular lobe in the maintenance of balance[35] although debate exists as to its cognitive, behavioural and motor functions.[36]

The cerebellum is divided into an anterior lobe, a posterior lobe, and the flocculonodular lobe.[31] The anterior and posterior lobes are connected in the middle by the vermis.[32] Compared to the cerebral cortex, the cerebellum has a much thinner outer cortex that is narrowly furrowed into numerous curved transverse fissures.[32] Viewed from underneath between the two lobes is the third lobe the flocculonodular lobe.[33] The cerebellum rests at the back of the cranial cavity, lying beneath the occipital lobes, and is separated from these by the cerebellar tentorium, a sheet of fibre.[34]

It is connected to the brainstem by three pairs of nerve tracts called cerebellar peduncles. The superior pair connects to the midbrain; the middle pair connects to the medulla, and the inferior pair connects to the pons.[32] The cerebellum consists of an inner medulla of white matter and an outer cortex of richly folded grey matter.[34] The cerebellum's anterior and posterior lobes appear to play a role in the coordination and smoothing of complex motor movements, and the flocculonodular lobe in the maintenance of balance[35] although debate exists as to its cognitive, behavioural and motor functions.[36]

Brainstem

The brainstem lies beneath the cerebrum and consists of the midbrain, pons and medulla. It lies in the back part of the skull, resting on the part of the base known as the clivus, and ends at the foramen magnum, a large opening in the occipital bone. The brainstem continues below this as the spinal cord,[37] protected by the vertebral column.

Ten of the twelve pairs of cranial nerves[a] emerge directly from the brainstem.[37] The brainstem also contains many cranial nerve nuclei and nuclei of peripheral nerves, as well as nuclei involved in the regulation of many essential processes including breathing, control of eye movements and balance.[38][37] The reticular formation, a network of nuclei of ill-defined formation, is present within and along the length of the brainstem.[37] Many nerve tracts, which transmit information to and from the cerebral cortex to the rest of the body, pass through the brainstem.[37]

The brainstem lies beneath the cerebrum and consists of the midbrain, pons and medulla. It lies in the back part of the skull, resting on the part of the base known as the clivus, and ends at the foramen magnum, a large opening in the occipital bone. The brainstem continues below this as the spinal cord,[37] protected by the vertebral column.

Ten of the twelve pairs of cranial nerves[a] emerge directly from the brainstem.[37] The brainstem also contains many cranial nerve nuclei and nuclei of peripheral nerves, as well as nuclei involved in the regulation of many essential processes including breathing, control of eye movements and balance.[38][37] The reticular formation, a network of nuclei of ill-defined formation, is present within and along the length of the brainstem.[37] Many nerve tracts, which transmit information to and from the cerebral cortex to the rest of the body, pass through the brainstem.[37]

Microanatomy

The human brain is primarily composed of neurons, glial cells, neural stem cells, and blood vessels. Types of neuron include interneurons, pyramidal cells including Betz cells, motor neurons (upper and lower motor neurons), and cerebellar Purkinje cells. Betz cells are the largest cells (by size of cell body) in the nervous system.[39] The adult human brain is estimated to contain 86±8 billion neurons, with a roughly equal number (85±10 billion) of non-neuronal cells.[40] Out of these neurons, 16 billion (19%) are located in the cerebral cortex, and 69 billion (80%) are in the cerebellum.[4][40]

Types of glial cell are astrocytes (including Bergmann glia), oligodendrocytes, ependymal cells (including tanycytes), radial glial cells, microglia, and a subtype of oligodendrocyte progenitor cells. Astrocytes are the largest of the glial cells. They are stellate cells with many processes radiating from their cell bodies. Some of these processes end as perivascular end-feet on capillary walls.[41] The glia limitans of the cortex is made up of astrocyte foot processes that serve in part to contain the cells of the brain.[13]

Mast cells are white blood cells that interact in the neuroimmune system in the brain.[42] Mast cells in the central nervous system are present in a number of structures including the meninges;[42] they mediate neuroimmune responses in inflammatory conditions and help to maintain the blood–brain barrier, particularly in brain regions where the barrier is absent.[42][43] Mast cells serve the same general functions in the body and central nervous system, such as effecting or regulating allergic responses, innate and adaptive immunity, autoimmunity, and inflammation.[42] Mast cells serve as the main effector cell through which pathogens can affect the biochemical signaling that takes place between the gastrointestinal tract and the central nervous system.[44][45]

Some 400 genes are shown to be brain-specific. In all neurons, ELAVL3 is expressed, and in pyramidal neurons, NRGN and REEP2 are also expressed. GAD1 – essential for the biosynthesis of the neurotransmitter GABA – is expressed in interneurons. Proteins expressed in glial cells include astrocyte markers GFAP and S100B whereas myelin basic protein and the transcription factor OLIG2 are expressed in oligodendrocytes.[46]

The human brain is primarily composed of neurons, glial cells, neural stem cells, and blood vessels. Types of neuron include interneurons, pyramidal cells including Betz cells, motor neurons (upper and lower motor neurons), and cerebellar Purkinje cells. Betz cells are the largest cells (by size of cell body) in the nervous system.[39] The adult human brain is estimated to contain 86±8 billion neurons, with a roughly equal number (85±10 billion) of non-neuronal cells.[40] Out of these neurons, 16 billion (19%) are located in the cerebral cortex, and 69 billion (80%) are in the cerebellum.[4][40]

Types of glial cell are astrocytes (including Bergmann glia), oligodendrocytes, ependymal cells (including tanycytes), radial glial cells, microglia, and a subtype of oligodendrocyte progenitor cells. Astrocytes are the largest of the glial cells. They are stellate cells with many processes radiating from their cell bodies. Some of these processes end as perivascular end-feet on capillary walls.[41] The glia limitans of the cortex is made up of astrocyte foot processes that serve in part to contain the cells of the brain.[13]

Mast cells are white blood cells that interact in the neuroimmune system in the brain.[42] Mast cells in the central nervous system are present in a number of structures including the meninges;[42] they mediate neuroimmune responses in inflammatory conditions and help to maintain the blood–brain barrier, particularly in brain regions where the barrier is absent.[42][43] Mast cells serve the same general functions in the body and central nervous system, such as effecting or regulating allergic responses, innate and adaptive immunity, autoimmunity, and inflammation.[42] Mast cells serve as the main effector cell through which pathogens can affect the biochemical signaling that takes place between the gastrointestinal tract and the central nervous system.[44][45]

Some 400 genes are shown to be brain-specific. In all neurons, ELAVL3 is expressed, and in pyramidal neurons, NRGN and REEP2 are also expressed. GAD1 – essential for the biosynthesis of the neurotransmitter GABA – is expressed in interneurons. Proteins expressed in glial cells include astrocyte markers GFAP and S100B whereas myelin basic protein and the transcription factor OLIG2 are expressed in oligodendrocytes.[46]

Cerebrospinal fluid

Cerebrospinal fluid is a clear, colourless transcellular fluid that circulates around the brain in the subarachnoid space, in the ventricular system, and in the central canal of the spinal cord. It also fills some gaps in the subarachnoid space, known as subarachnoid cisterns.[47] The four ventricles, two lateral, a third, and a fourth ventricle, all contain a choroid plexus that produces cerebrospinal fluid.[48] The third ventricle lies in the midline and is connected to the lateral ventricles.[47] A single duct, the cerebral aqueduct between the pons and the cerebellum, connects the third ventricle to the fourth ventricle.[49] Three separate openings, the middle and two lateral apertures, drain the cerebrospinal fluid from the fourth ventricle to the cisterna magna one of the major cisterns. From here, cerebrospinal fluid circulates around the brain and spinal cord in the subarachnoid space, between the arachnoid mater and pia mater.[47] At any one time, there is about 150mL of cerebrospinal fluid – most within the subarachnoid space. It is constantly being regenerated and absorbed, and is replaced about once every 5–6 hours.[47]

A glymphatic system has been described[50][51][52] as the lymphatic drainage system of the brain. The brain-wide glymphatic pathway includes drainage routes from the cerebrospinal fluid, and from the meningeal lymphatic vessels that are associated with the dural sinuses, and run alongside the cerebral blood vessels.[53][54] The pathway drains interstitial fluid from the tissue of the brain.[54]

Cerebrospinal fluid is a clear, colourless transcellular fluid that circulates around the brain in the subarachnoid space, in the ventricular system, and in the central canal of the spinal cord. It also fills some gaps in the subarachnoid space, known as subarachnoid cisterns.[47] The four ventricles, two lateral, a third, and a fourth ventricle, all contain a choroid plexus that produces cerebrospinal fluid.[48] The third ventricle lies in the midline and is connected to the lateral ventricles.[47] A single duct, the cerebral aqueduct between the pons and the cerebellum, connects the third ventricle to the fourth ventricle.[49] Three separate openings, the middle and two lateral apertures, drain the cerebrospinal fluid from the fourth ventricle to the cisterna magna one of the major cisterns. From here, cerebrospinal fluid circulates around the brain and spinal cord in the subarachnoid space, between the arachnoid mater and pia mater.[47] At any one time, there is about 150mL of cerebrospinal fluid – most within the subarachnoid space. It is constantly being regenerated and absorbed, and is replaced about once every 5–6 hours.[47]

A glymphatic system has been described[50][51][52] as the lymphatic drainage system of the brain. The brain-wide glymphatic pathway includes drainage routes from the cerebrospinal fluid, and from the meningeal lymphatic vessels that are associated with the dural sinuses, and run alongside the cerebral blood vessels.[53][54] The pathway drains interstitial fluid from the tissue of the brain.[54]

Blood supply

The internal carotid arteries supply oxygenated blood to the front of the brain and the vertebral arteries supply blood to the back of the brain.[55] These two circulations join in the circle of Willis, a ring of connected arteries that lies in the interpeduncular cistern between the midbrain and pons.[56]

The internal carotid arteries are branches of the common carotid arteries. They enter the cranium through the carotid canal, travel through the cavernous sinus and enter the subarachnoid space.[57] They then enter the circle of Willis, with two branches, the anterior cerebral arteries emerging. These branches travel forward and then upward along the longitudinal fissure, and supply the front and midline parts of the brain.[58] One or more small anterior communicating arteries join the two anterior cerebral arteries shortly after they emerge as branches.[58] The internal carotid arteries continue forward as the middle cerebral arteries. They travel sideways along the sphenoid bone of the eye socket, then upwards through the insula cortex, where final branches arise. The middle cerebral arteries send branches along their length.[57]

The vertebral arteries emerge as branches of the left and right subclavian arteries. They travel upward through transverse foramina which are spaces in the cervical vertebrae. Each side enters the cranial cavity through the foramen magnum along the corresponding side of the medulla.[57] They give off one of the three cerebellar branches. The vertebral arteries join in front of the middle part of the medulla to form the larger basilar artery, which sends multiple branches to supply the medulla and pons, and the two other anterior and superior cerebellar branches.[59] Finally, the basilar artery divides into two posterior cerebral arteries. These travel outwards, around the superior cerebellar peduncles, and along the top of the cerebellar tentorium, where it sends branches to supply the temporal and occipital lobes.[59] Each posterior cerebral artery sends a small posterior communicating artery to join with the internal carotid arteries.

The internal carotid arteries supply oxygenated blood to the front of the brain and the vertebral arteries supply blood to the back of the brain.[55] These two circulations join in the circle of Willis, a ring of connected arteries that lies in the interpeduncular cistern between the midbrain and pons.[56]

The internal carotid arteries are branches of the common carotid arteries. They enter the cranium through the carotid canal, travel through the cavernous sinus and enter the subarachnoid space.[57] They then enter the circle of Willis, with two branches, the anterior cerebral arteries emerging. These branches travel forward and then upward along the longitudinal fissure, and supply the front and midline parts of the brain.[58] One or more small anterior communicating arteries join the two anterior cerebral arteries shortly after they emerge as branches.[58] The internal carotid arteries continue forward as the middle cerebral arteries. They travel sideways along the sphenoid bone of the eye socket, then upwards through the insula cortex, where final branches arise. The middle cerebral arteries send branches along their length.[57]